As I discussed in a post last month, I recently took a Coursera class on network theory and analysis. I did this in part because I wanted to evaluate the MOOC format from a student’s perspective. But I also did it because network theory is very hot right now and appeals to my old life as a mathematician.

During the first couple of weeks of the class I decided that I needed a real-life network to play around with. Inspired by this post, I decided to look at the history of philosophy as described by the “influence” relationship in Wikipedia. I plan to write a paper — maybe for a digital humanities project — on my findings, complete with some background on network theory for non-philosophers. Here I’m going to skip the technical details and show you some pretty pictures and some basic results about identifying the “most influential” philosophers.

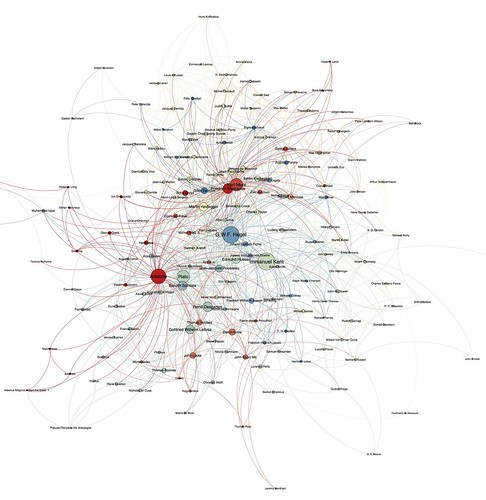

My dataset is large by the standards of the traditional humanities, though not so large by the standards of many digital humanities projects and tiny compared to, say, a genome sequence. The base graph contains 1,997 distinct philosophers (assuming no repeats — one step in acquiring the dataset consolidates repeats, but I have to identify these manually) with 4,022 connections between them. Connections represent one philosopher influencing another. Because of this size, pretty much any effort to represent the entire graph is an incomprehensible mess. So here’s a picture of the 177 philosophers in the dataset who are connected to at least 10 other philosophers.

The size of the circle indicates something called the eigenvector centrality of the node in the network — one of the measures of influence that I investigated and will discuss below. The color picks out distinct communities of highly-inter-connected philosophers, though I think the algorithm used to determine this doesn’t work so well for this particular network.

The post that I linked to in the second paragraph did this much. But I wanted to use some of the tools for quantitative analysis that I was learning in my course. Since the contemporary culture of philosophy seems to care a lot about ranking — programs, schools, journals, individual philosophers — I decided to focus on that.

From a network perspective, one obvious ranking question to ask is “how well-connected is each node to the rest of the network?” These are measures of the centrality of nodes. And there are several different ways to do it. One way is simply to measure the number of immediate connections, or neighbors, that a node has. More sophisticated ways look at the node within the overall structure of the network. I used three measures of centrality: out-degree, the number of philosophers directly influenced by the given philosopher; betweenness, which looks at the position of the given philosopher along distant connections in the network; and eigenvector, which looks at how well-connected the given philosopher is to other well-connected philosophers. Here are the rankings:

| Out-degree | Betweenness | Eigenvector | Condorcet | Leiter “Most Important” | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kant | 1 | 2 | 1 | 44 | 3 |

| 1. Hegel | 3 | 1 | 2 | 42 | 11 |

| 3. Marx | 4 | 5 | 4 | 35 | 17 |

| 4. Aristotle | 2 | 3 | 27 | 2 | |

| 4. Descartes | 11 | 4 | 7 | 26 | 5 |

| 6. Plato | 5 | 16 | 5 | 22 | 1 |

| 6. Nietzsche | 6 | 6 | 20 | 18 | |

| 6. Heidegger | 8 | 10 | 10 | 20 | |

| 6. Leibniz | 3 | 9 | 20 | 12 | |

| 6. Spinoza | 14 | 6 | 8 | 20 | 13 |

| 11. Hume | 13 | 7 | 15 | 13 | 4 |

| 11. Rousseau | 8 | 12 | 12 | 20 | |

| 11. Husserl | 10 | 15 | 11 | 12 | |

| 14. Wittgenstein | 7 | 9 | 7 | ||

| 14. Aquinas | 9 | 7 | 10 | ||

| 14. Mill | 9 | 7 | 14 |

(Sorry this looks like crap — Tumblr seems to be eating my style tags. Blanks indicate that the given philosopher wasn’t ranked in the top-20 by that centrality measure. I’m going to come back to the final column.) The first thing that I notice is that there is both significant agreement and significant disagreement among these rankings. All three agree that Kant and Hegel are at the top, followed a little ways by Marx, and Heidegger near the bottom of the top-10. But there’s also significant disagreement about who comes in the middle.

To some extent, this is probably due to the way the different measures work. For example, Ancient philosophers have a disadvantage on the betweenness measure: most of the philosophers in the network came centuries later, and so the Ancient philosophers don’t mediate many connections. I want to discuss this further in the paper.

To aggregate these three lists, I used a variation on Condorcet polling. In a Condorcet poll, each voter ranks all of the candidates in order of preference; we then aggregate these votes by seeing how among how many voters each candidate beats the others. Here I used the three lists as my three voters, and replaced the one-to-one comparisons of a Condorcet poll with a simpler counting scheme. For example, Hegel outranks the other 15 a total of 42 times among the three lists; Marx outranks the other 15 a total of only 35 times, and so comes below Hegel. We can then assign rankings, ignoring differences of 2 “points” or less.

Finally, it’s interesting to contrast these rankings with the results of a poll on the “most important philosophers of all time,” conducted by Brian Leiter on his blog in 2009. That’s the final column of the table above. Compared to my analysis, Leiter’s poll ranks Plato significantly higher, and ranks Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche significantly lower. Heidegger and Husserl don’t even show up in Leiter’s top-20; conversely, my top-20 doesn’t include Socrates, Locke, and Frege.

What could explain this difference? My dataset ultimately comes from Wikipedia; Leiter’s comes from the readers of his blog. Insofar as “anyone can edit a Wikipedia page” and Leiter’s audience is primarily professional philosophers, it seems reasonable to think that this probably explains a lot of the difference: professional philosophers generally think less of Heidegger and Husserl, and more of Plato and Frege, than the “anyone” who is editing the Wikipedia pages on these philosophers.

Does this mean that Leiter’s rankings are, in some sense, better than the results of my analysis? I’m skeptical, for at least two reasons. First, the voters in Leiter’s poll knew that they were voting in a poll, and so simply a priori there’s the possibility of people voting multiple times or engaging in strategic voting to manipulate the results. The Wikipedia editors had no idea that I was going to carry out this analysis, and so it’s much less plausible to think that they might have tried to manipulate the dataset.

But that’s a minor concern. My second and deeper reason is it’s not clear what counts as a “better” ranking. We might think a better ranking is “more accurate”; but more accurate to what? Leiter asks which philosophers are “most important,” and it’s not clear to me that there’s an objective fact of the matter about whether Plato is more or less important than Marx. If the poll had been taken in the eighteenth century, Aristotle and Aquinas probably wouldn’t have even been candidates; late in the nineteenth century, Hegel would have been much closer to the top and Hume much further down. Furthermore, even if there is an objective fact of the matter, the poll’s methodology seems to be better designed to measure who is liked more by readers of Leiter’s blog than who is objectively more important.

My analysis is based on data about philosophical influence. It seems to me more plausible to think that these data are more objective than importance. But influence is quite vague. Is it reasonable to say that Descartes was influenced by Aristotle or al-Ghazali? What about someone like John Rawls, who was arguably influenced by a hundred different thinkers in the history of ethics, but in the dataset is only influenced by Locke? Furthermore, we have to draw disciplinary boundaries somehow. Should these be based on the boundaries of the contemporary university? Should we include Newton, or Thomas Kuhn?

At this point, it seems that we must take the purposes of the rankings into account. What question are we trying to answer, and why are we trying to answer it?