In October 2020, Nature published an editorial endorsing Joe Biden and criticizing Trump (“Why Nature Supports Joe Biden for US President” 2020). A few days ago, Nature Human Behavior published an online survey experimental study (Zhang 2023) that appeared to find that “some who saw the endorsement lost confidence in the journal as a result” (Lupia 2023). The study has prompted a lot of discussion on social media, especially after the editors of Nature stood by their decision to endorse Biden (“Should Nature Endorse Political Candidates? Yes — When the Occasion Demands It” 2023) and Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of Science, posted a short Twitter thread in agreement.

In many of these discussions, Zhang (2023) is being interpreted in terms of the value-free ideal (VFI). This interpretation is mistaken, because the Nature endorsement doesn’t violate VFI. It does violate a more general principle, but by putting Zhang (2023) in the context of my own empirical research I argue that violations of this principle don’t explain the headline findings. I develop a better explanation using another branch of my research, developing the “aims approach” to values in science.

A little background on me

Since I plan to share links to this post in social media threads with strangers, I thought it would be helpful to introduce myself and explain my expertise in this topic. I’m a philosopher of science and STS (science and technology studies) researcher at the University of California, Merced. As a philosopher of science I specialize in the subfield we call “science, values, and policy” or “science and values.” I’ve written a number of papers on the value-free ideal, why almost all contemporary philosophers of science reject it, and the implications this has for policy-based science. My work experience includes two years as a AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow, during which I worked at1 the US Environmental Protection Agency and the National Science Foundation. I also conduct empirical research, and recently published a collaboration with a cognitive psychologist that I’m going to discuss more below (Hicks and Lobato 2022).

The Nature endorsement doesn’t violate VFI

My first point is that neither the Nature endorsement nor the summary seen by the participants in Zhang (2023) violates VFI. The endorsement’s argument is straightforwardly political: Trump has made bad policy decisions, and Biden will make better ones.

No US president in recent history has so relentlessly attacked and undermined so many valuable institutions, from science agencies to the media, the courts, the Department of Justice — and even the electoral system. Trump claims to put ‘America First’. But in his response to the pandemic, Trump has put himself first, not America. (“Why Nature Supports Joe Biden for US President” 2020)

Philosophers of science define the value-free ideal strictly, as a norm prohibiting the influence of non-epistemic values2 in the “core” stages of scientific inquiry, especially the evaluation of hypotheses. While the Nature endorsement does make some claims that could be evaluated empirically as hypotheses, it’s not doing this empirical evaluation itself. Instead these claims are presented as premises in its argument that Trump has made bad policy decisions. So, there’s no violation of VFI here.

Zhang (2023) provided the participants (specifically, the ones in the intervention arm of the study) with this summary of the endorsement:

Scientific journal Nature endorsed Joe Biden

Weeks before the 2020 presidential election, Nature’s editorial board official endorsed Joe Biden, citing:

- Donald Trump’s pandemic response had been “disastrous”;

- Biden, unlike Trump, would listen to science, and thus;

- Biden would handle the COVID-19 pandemic better.

Nature is one of the most-cited and most prestigious peer-reviewed scientific journals in the world.

Zhang (2023) also included a screenshot of the endorsement headline and a link to the story. This summary also does not include a VFI violation.

The Nature endorsement does violate value neutrality (if it applies)

The Nature endorsement doesn’t violate VFI, but it does seem to violate a more general norm, value neutrality. Havstad and Brown give a nice definition in their analysis of the IPCC’s ambition to be “policy-relevant but policy-neutral”:

When making value judgments, parties who are objective in the sense of value-neutrality remain as neutral as possible where values are controversial, either by avoiding value judgments in that specific instance or by seeking balanced or conciliatory positions within the range of values. (Havstad and Brown 2017; see also H. Douglas 2004, 460)

Endorsing a candidate in a contested election is pretty much certain to involve controversial values.3 So the endorsement obviously violated this neutrality norm.

However, we might question whether value neutrality applies to the Nature editors in their role as editors. I take it that many people think value neutrality applies to journalists in their role as journalists, but also that newspaper endorsements of candidates are not regarded objectionable. This would mean that the value neutrality norm applies to journalists as journalists, but not as editors (perhaps with restrictions, for example, to clearly-labelled opinion pieces).

Since Nature is a science journal, its editors are likely to be thought of as scientists (I’m too lazy to check to what extent its editors do in fact have scientific backgrounds, and in any case I expect editing the journal is sufficiently demanding that they’re not doing much actual research), and I take it most people think value neutrality applies to scientists. Still, for the endorsement to violate value neutrality, the scope of the norm would have to be broader for scientists than for journalists.

Value neutrality might be confused for VFI because the former entails the latter, at least so long as we assume (incorrectly) “that epistemic values are politically neutral while non-epistemic values are politically controversial” and that value neutrality applies to scientists in the “core” stages of inquiry.

Should value neutrality apply to scientists in their roles as journal editors writing a clearly-labelled opinion piece? Given that this norm doesn’t apply to newspaper editors, I can’t think of a compelling reason to apply it to scientific journal editors. There are also the critiques of neutrality given by Havstad and Brown (2017); and because value neutrality (plus assumptions) entails VFI, the many compelling arguments against VFI also apply to value neutrality (unless one tries to preserve it by rejecting some of the assumptions instead).4 Though perhaps the results of Zhang (2023) give us a consequentialist argument for applying the norm to scientists in their roles as journal editors: violating value neutrality undermines public trust in science.

Zhang (2023): Findings and a concern about generalizability

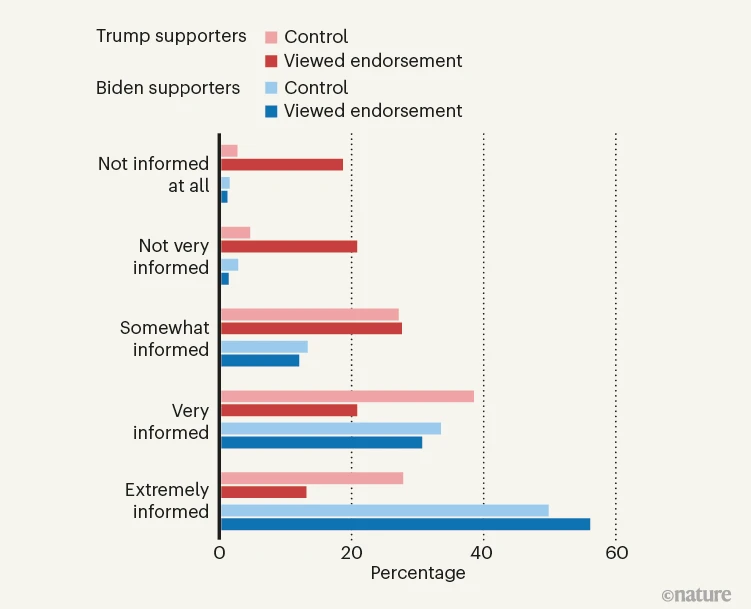

So let’s turn to Zhang (2023). The headline finding — as communicated with some really bad data visualization — was that Trump voters who saw the Nature endorsement summary in the experiment rated Nature editors as much less informed and much more biased, compared to Trump voters in the control condition. Treating the five-point Likert scale as a continuous one, the treatment effect was about -0.9 for informed and 0.6 for biased; that is, about a full point drop for informed and more than half a point for biased. Trump voters who saw the endorsement were also substantially less likely to get covid-19 information from Nature, again compared to Trump voters in the control condition.5 Importantly, these effects were only observed for Trump voters. There was no sign of similar effects for Biden voters.

Much of the commentary around Zhang (2023) is generalizing this headline finding, to a claim that the endorsement undermined trust in science generally. Zhang (2023) did examine this generalization, and did find statistically significant results for Trump voters. However, these effects were much smaller in magnitude, about 0.15 on the five-point Likert scale. This means that a few Trump voters saw science generally as a little less trustworthy after seeing the endorsement, but overall this effect is negligible. An old complaint in statistics is that “practical significance is different from statistical significance.”

Zhang (2023) would still be worrisome, insofar as one is worried that violations of neutrality could undermine trust in individual or well-defined groups of scientists (eg, the IPCC). But I don’t think we need to worry about the Nature endorsement undermining trust in science in general.

The Zhang (2023) results aren’t explained by VFI or neutrality violations

My overall claim in this post is that violations of neither VFI nor neutrality provide a good explanation of the findings of Zhang (2023). The first argument against VFI is that, as I discussed above, the endorsement doesn’t violate VFI. It’s hard to use a norm violation to explain these findings if the norm wasn’t violation. We could make a similar argument against a neutrality-based explanation if it turned out that most people (or Trump voters specifically) don’t think this norm applies to science journal editors when writing clearly-labelled opinion pieces.

I doubt that will be a compelling argument to many readers, though. My second argument starts by noting that there was no effect for Biden voters. If VFI and/or value neutrality violations explained these findings, we would expect to see effects for both Trump and Biden voters. But we don’t, so they don’t.

One potential response to this argument would be to posit an interaction model, on which the norm is evaluated differently by Trump vs. Biden voters. Matt Weiner and Kevin Zollman gave versions of this response on Twitter, in a thread started by João Ohara. In particular, my reading of Zollman’s version is that VFI applies if and only if the scientist does not share one’s values. So, for Trump voters, the Nature editors don’t share the participant’s values, so VFI applies, and so the Nature editors violated VFI. On the other hand, for Biden voters, the Nature editors do share the participant’s values, so VFI does not apply, and so the Nature editors did not violate VFI. Call this the shared values VFI model. (For the reasons given above, we should probably focus on a neutrality version of this explanation, rather than VFI. However, for simplicity, throughout the rest of the post I’m often going to use VFI as an umbrella term that includes neutrality.)

It would be difficult to study empirically whether and how VFI was playing a role in participants’ reactions to the endorsement. It wouldn’t be enough to simply ask participants whether they accept VFI (written in a way that a general audience can understand) and then run the same experiment as Zhang (2023), because that wouldn’t get at the question of whether and how the participants are reasoning with VFI when they encounter the endorsement. There would also be a serious risk of priming effects, whichever order the questions were presented: seeing VFI first might make participants more likely to use it to react to the endorsement, while seeing the endorsement first might change their acceptance of VFI insofar as they see it as supporting or challenging their reaction to the endorsement. Qualitative methods — having participants narrate their reasoning about the endorsement, either out loud or in writing — could actually get at whether and how VFI is playing a role without worrying about priming. Though these methods are extremely labor intensive. None of this is a reason to think the shared values VFI model is false, of course. But it is reason to think this model is not pursuitworthy, which in turn is a reason to not accept it.

Conflicting results from Hicks and Lobato (2022)

Another problem with the shared values VFI model for the findings of Zhang (2023) is it conflicts with the results of a pair of extremely similar studies, Elliott et al. (2017) and Hicks and Lobato (2022). The latter paper is an independent replication of the former, using the same experimental design but a larger sample (slightly under 500 vs. slightly under 1,000 participants) from a more reliable pool (Amazon Mechanical Turk vs. a representative sample of US adults from the polling firm Prolific).

In both studies, participants were told that bisphenol A (BPA) is a controversial chemical, and shown a slide attributed to a (fictional) scientist, Dr. Riley Spence. The contents of the side differed by condition; here’s one example:

My conclusion

- Protecting public health should be a top national priority.

- I examined the scientific evidence on potential health risks of BPA.

- I conclude that BPA in consumer products is causing harm to people.

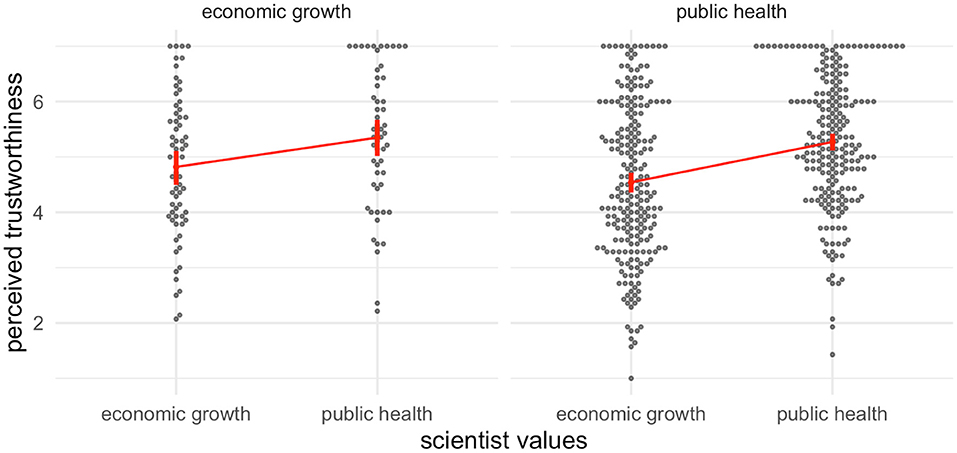

The first bullet point had three possibilities: either “protecting public health” (in this case), “promoting economic growth,” or this bullet was missing entirely. The third bullet had two possibilities, either “causing harm” (in this case) or “not causing harm.”6 Participants then filled out the Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI; Hendriks, Kienhues, and Bromme 2015) to assess the perceived trustworthiness of Dr. Spence.7 Participants were also asked for their own views on the tradeoff between public health and economic growth.

Hopefully it’s obvious how similar this study design is to Zhang (2023); they’re so similar I’m a little disappointed that neither paper was cited! Both designs have a clear violation of neutrality. Zhang (2023) does have a much larger sample size (over 4,000 participants) than either of the Riley Spence design studies. But in every other respect I think the Riley Spence design is better for examining the effects of violations of VFI or neutrality: the value judgments are stated explicitly, rather than implied by partisan alignment; those values have a clear partisan valence but the topic isn’t emotionally heated (this will be important in the next section); and the conclusion is a scientific claim rather than a political one.8 The one major limitation in the Riley Spence design is that this isn’t an unambiguous violation of VFI; though to me including a value statement on the concluding slide of a presentation does implicate a VFI violation. And of course the prompt in Zhang (2023) doesn’t include a violation of VFI either.

An additional, important advantage of the Riley Spence design is that it can distinguish shared values from the “first order” value held by the participant (whether the participant prioritizes public health or economic growth). This means this design can test a version of the shared values VFI model. We examine a “shared values” effect: given that the scientist discloses values, then “if the participant and scientist share the same values, the scientist is perceived as more trustworthy than if the participant and scientist do not share the same values” (Hicks and Lobato 2022, 05). This doesn’t get at why shared values have this different effect — whether the participant is using VFI conditional on shared values or doing something else — but it does allow us to look for a shared values effect independent of which values the participant holds. Because Zhang (2023) doesn’t have a Republican values arm, it can’t separate these potential effects.

Two findings of Elliott et al. (2017) would seem to support Zhang (2023) and the alternative explanation: they report a loss of perceived trust for a scientist who discloses values, compared to one who does not; and a shared values effect. However, Hicks and Lobato (2022) does not find evidence for either effect, and shows that the shared values finding was an artifact of the unusual analytic approach taken by Elliott et al. (2017; Hicks and Lobato 2022, 10).

Consider first a reduction in trust for violating neutrality and disclosing a value judgment. Zhang (2023)’s estimate for this effect (for the “informed” item) is -0.85 on a 5-point scale (95% CI roughly -0.75 to -0.95), which would be about -1.19 (-1.05 to -1.33) if we (crudely) rescaled to the 7-point scales used in both the Riley Spence papers. Elliott et al. (2017)’s data gives an estimate of -0.5 (-.3, -0.8), and Hicks and Lobato (2022) estimate (0.0, -0.3). The more careful Riley Spence design yields much smaller effects than the design in Zhang (2023). I’ll come back to the question of how we might explain differences in these estimates in the final section.

Suppose we side with Zhang (2023) (despite the lower-quality design) and Elliott et al. (2017) (despite the smaller and lower-quality sample) over Hicks and Lobato (2022), and judge that the total evidence favors an decline of trust from violating neutrality. Might an interaction between shared values and VFI be at work here? Again, Elliott et al. (2017) report a shared values effect. But Hicks and Lobato (2022) show that, when their data are re-analyzed using a more conventional method, there is no evidence of such an effect. What’s more, the data from both of these papers do support a “scientist values” effect: given that the scientist discloses values (violates neutrality), a scientist who values public health is perceived as more trustworthy than one who values economic growth, even by participants who prioritize economic growth.

Because the Riley Spence design can separate shared and partisan values, while the design in Zhang (2023) cannot, I think the Riley Spence design provides much more relevant and reliable evidence regarding a shared values VFI model. And so I think the findings from Elliott et al. (2017) and Hicks and Lobato (2022) are a major challenge to that model.

The aims of science

Based on study quality features, I think Hicks and Lobato (2022) provides the strongest evidence among the three studies I’ve reviewed here; and this study finds evidence against both the “simple” VFI model and the more complex shared values VFI model. Of course I have a conflict of interest, and rather than simply declaring Hicks and Lobato (2022) the “winner” a better approach would be to develop a model that can explain why Zhang (2023) and Hicks and Lobato (2022) produced different results (Heather Douglas 2012).

Following the discussion in Hicks and Lobato (2022), I suggest that the “aims approach” to values in science can provide a model that explains all of the results. On this approach, we start by recognizing that scientific research typically has a mix of epistemic and practical aims. For example, the aim of environmental epidemiology is not just to understand how pollution harms human health, but also to develop policies that reduce pollution and its health impacts. Proponents of this approach argue that the practical aims can play legitimate roles in all stages of scientific inquiry, even when evaluating hypotheses (Fernández Pinto and Hicks 2019; Hicks 2022).

In Hicks and Lobato (2022), we use this approach to explain the scientist values effect. We posit that almost all participants — even ones who prioritize economic growth — recognize protecting public health as one of the aims of environmental public health, while promoting economic growth is not among its aims. So a scientist who prioritizes public health is acting appropriately, while a scientist who prioritizes economic growth is not, regardless of the participant’s own priorities.

In Zhang (2023), I suggest that Trump and Biden voters saw the implied aims of the Nature editors very differently. Again, in the summary of the endorsement, the argument for endorsing Biden was that “Donald Trump’s pandemic response had been ‘disastrous’”; “Biden, unlike Trump, would listen to science”; and “Biden would handle the COVID-19 pandemic better.” I suggest that, for Biden voters, this argument communicated the legitimate scientific aim of informing public policy to promote public health. On the other hand, I suggest that many Trump voters would read this argument as scientists trying to shift blame from scientific authorities (CDC, NIH) to Trump, calling for even more power and influence than they already have, and trying to justify policies that these voters saw as creeping authoritarianism (stay-at-home orders, restrictions on restaurants and other businesses, mask and vaccination requirements). None of these are legitimate scientific aims.

On this model, shared values don’t play a role in any of these studies. The participants’ values (more properly, the participants’ epistemic community and their interpretive frames) can play a role, but early on, when the participant reads the stimulus. But then it’s the scientist’s values that matter, and whether those values align or conflict with the aims of science, not whether the align or conflict with the participants’ values.

And neither neutrality nor VFI play a role in this model. The aims approach has been developed as an alternative to VFI (and neutrality), to explain how scientists legitimately use non-epistemic values throughout their research.

References

Footnotes

Technically “at,” not “for.”↩︎

It’s common in the literature to use “non-epistemic values” interchangeably with something like “social and political values.” But I think this is incorrect, because — on my preferred definition of epistemic values, namely, features of scientific practice that promote the pursuit of epistemic aims such as truth and understanding — social and political values can sometimes be epistemic (Hicks 2022, esp. pages 1-2).↩︎

This is actually tricky in the Nature endorsement, because their value judgments are bundled into thick claims. For example, one of their premises is that Trump’s management of the pandemic was “disastrous.” This is a thick concept, with both descriptive criteria for application and evaluative implications: Trump’s handling of the pandemic resulted in hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths, and this is a severely bad thing. (Note that “preventable death” is another thick concept.) The controversy here isn’t over the evaluative side, the idea that preventable deaths are bad. Instead it’s over the descriptive side: that Trump’s handling of the pandemic had these effects.↩︎

Specifically, someone might try to concede VFI and preserve value neutrality by rejecting the alignment between epistemic/non-epistemic and neutral/controversial values. Schroeder (n.d.) might potentially be read in this way: democratically-endorsed non-epistemic values are treated as not controversial, and so appealing to them does not violate neutrality.↩︎

I’m confused by the scale used in reporting this effect, so I’m just calling it “substantial” here.↩︎

Varying these independently means that we can distinguish any effects related to the value judgment from effects of the conclusion. The design in Zhang (2023) can’t do this, because in a sense the value judgment is the conclusion.↩︎

One incidental concern about Zhang (2023) is that they used a single item for every variable of interest. They did ask about two aspects of trustworthiness, whether the trustee was informed and whether they were biased. But that was done using exactly two questions, and responses weren’t combined. Psychologists seem to prefer multi-item instruments. For example, the METI has 14 items covering three aspects of trustworthiness: competence, benevolence, and integrity. I’m not entirely sure why psychologists prefer multi-item instruments, though, so I decided not to discuss it in the body of the post.↩︎

Elliott et al. (2017) report a second study with a policy conclusion, namely, whether BPA should be regulated. Due to limited funds my collaborator and I didn’t replicate this part.↩︎